2024 SPRING Vol.72

Stories about modern history

All sorts of emotions (喜怒哀樂) of ‘coal,’ the number one contributor to Korea’s economic development

Just as Prometheus brought the torch to mankind, coal was the greatest gift to civilization.

While petroleum acted as the nobility among fossil fuels, coal has long been a warm neighbor to common people. While there were records of mankind's use of coal in BC literature, it was around the time of the Industrial Revolution when coal began to gain prominence. During the Industrial Revolution, mechanical facilities, as well as railroads and steam locomotives, were all powered by coal. In this column, we will look at all sorts of emotions of coal, which has been a major contributor to Korea’s economic development.

Coal saved Korea's economy

Coal mines in South Korea, such as the Mungyeong mining office and the Hwasun mining office, were developed around the Japanese colonial period, and miners from three ethnic groups, Korean, Japanese, and Chinese, worked together to produce them. Furthermore, while hundreds of thousands of miners were conscripted to work in Japanese coal mines, they voluntarily went to work as miners in Germany after liberation, demonstrating the Korean coal mining diaspora as a unique phenomenon because nothing was like it in global mining history. The honor of being an ‘industrial warrior’ was given to miners, another title of the National Service Draft Ordinance that was created by Japanese imperialism to secure labor during the Asia-Pacific War. Consistent with the connection between combat and production, the so-called industrial warriors were forced to produce coal under the pretext of patriotism. Coal became an essential energy resource for national industrial development. Even during the Korean War, Korea established the Korea Coal Corporation, and securing coal was a national task that miners had to do throughout the war. To increase coal production, model industrial warriors were selected and invited to the President's official residence, or were honored at a three-day consolation event in Seoul in the mid-1950s. When oil prices fell in the late 1960s, a policy to use petroleum as the main fuel and coal as an auxiliary fuel was implemented, causing many coal mines to close. However, the country quickly returned to the coal era. This was due to the first oil crisis caused by the Middle East war in 1973, which led to a surge in briquette consumption due to the abnormal cold wave in 1977, and the second oil crisis resulting from Iran's bloody revolution the following year. In coal mines, miners were pushed through policies such as long shifts, rapid tunneling1), and allocation of production responsibilities. There was a competition to scout miners at each mining office, with the briquette factory operating all night to transport briquettes. Coal was a national energy source that saved Korea's economy in the aftermath of the global oil crisis.

The savior of railway development and balanced national development

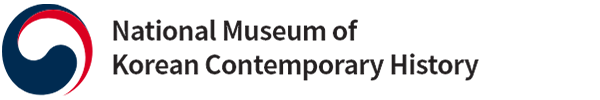

During the Japanese colonial period, all the coal produced by Taebaek's Jangseong mining office and Samcheok's Dogye mining office was plundered by Japan through Mukho Port. In May 1948, North Korea halted power transmission after South Korea established an independent government, leading to a shortage of coal to operate the Yeongwol thermal power plant. There were large mining offices in Taebaek and Samcheok, but there were no transportation routes. The railway was only opened between Taebaek and Mukho Port to transport coal to Japan. In the end, it was finally possible to operate the Yeongwol thermal power plant after a three-day detour: coal from Taebaek and Samcheok was transported by train to Mukho Port, from Mukho Port to Incheon Port via the Namhae by ship, and from Incheon to Yeongwol by rail. This story is evidence that the coal mines of Taebaek and Samcheok were developed by the Japanese to exploit Korea’s coal resources, and showed how important it was to open an industrial railway to transport coal. Because of coal, the Yeongam Line (Yeongju-Cheoram), which even deployed the Army Corps of Engineers, was rushed to open in 1955, the Jecheon-Yeongwol-Hambaek section in 1957, and the Jecheon-Taebaek section in 1973. Expanding the railroad network for coal transportation was important to the country, to the extent that the president personally attended the railway opening and test ride ceremony. The Mungyeong Line in Gyeongbuk was also built as an industrial railway to transport coal. Thus, coal is the savior of railway development and balanced national development.

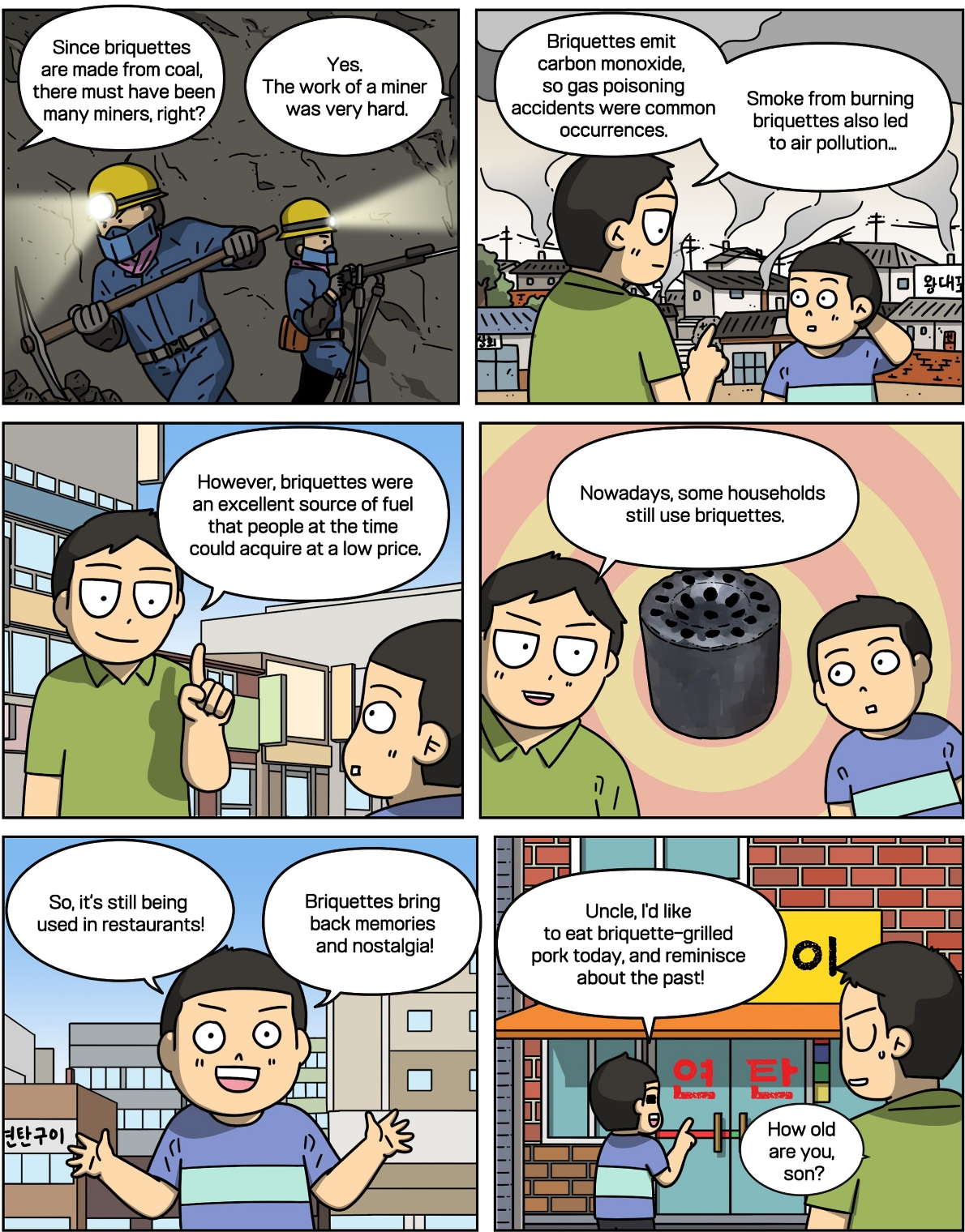

The public interest in briquettes that even save forests

Briquettes, along with kimchi, were the number one item for winter preparation. Before 1986, the number of households heating with briquettes in Korea exceeded 80%. The price of briquette did not rise as much for several decades, a consideration for the common people. The supply of cheap briquettes stopped the practice of cutting down trees for firewood, and coal mines that used to rely on tree trunks began actively cultivating forests, allowing us to maintain the dense forests we have today. Forest recreation and forest healing programs, which have become popular recently, were possible because of briquettes.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, briquette shortages occurred every winter. In 1966, the first prize in a broadcasting company's contest was a briquette, and, in 1969, the president instructed ministers to put their ministerial positions on the line and implement the briquette supply plan. In the mid-1970s, due to a shortage of briquettes, the government implemented a briquette purchase card system, and controlled its supply through a distribution system. There were various nicknames for briquettes, such as honeycomb briquette, nine-holed briquette, and 19-holed briquette. The name honeycomb briquette comes from the air holes drilled to allow the briquettes to burn well, and the nickname nine-holed briquette comes from the fact that the first briquettes had nine holes. The more holes there are, the larger the size of the briquette, with up to 49-hole briquettes. The most popular briquettes are the 19-hole briquette and the 22-hole briquette.

Will a coal-mining town be listed as a UNESCO inscribed on the World Heritage Site?

With the closure of the Dogye Mining Office in 2025, Korea Coal Corporation will shut down all mining offices, but the ‘Commission for the Promotion of Industrial Warriors Memorial and Sanctuary‘ will be launching a movement to enact a special law that will call for the enactment of Coal Miner's Day. Coal Miner's Day has already been established in many countries, including North Korea, the United States, Russia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, and Poland. If Coal Miner's Day is established in Korea, coal industry warriors will receive great comfort. In Samcheok and in Taebaek, a movement is underway to register the entire coal-mining town as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Measures are being taken to ensure the cultural identity of the coal-mining town, which is Korea's representative industrial community along with other farming and fishing villages, and to preserve the sites of the Jangseong Mining Office and the Dogye Mining Office, which were core business offices of the Coal Corporation. Like Samtan Art Mine2) in Jeongseon, where an abandoned mine facility was transformed into an art space, listing the coal industrial heritage as a UNESCO World Heritage site will be a process of re-resourcing the coal heritage. The coal industry, which was the driving force that helped turn Korea into an economic powerhouse after overcoming Japanese colonial rule and the Korean War, is more than qualified to be recognized by UNESCO. Although the era is at the end of the coal mine, we believe that the precious value of ‘coal-briquettes’ that industrial warriors mined from the blind end will be permanently cited through UNESCO registration.

Coal Mine Arirang

- Jeong Yeon-soo

Arirang Arirang Arariyo at the blind end

I can easily get over Nobori Ridge without a camp lamp

Coal-mining town Ridge is a padlocked Ridge

I will go after three years, five years, thirty years have passed

Even if I dig a mine and make money, I won't be able to see the sunlight

Alcohol tab from day one, severance pay is full of debt

Coal-mining town ridge is a living hell ridge

After carrying the round timber on my waist, my spine sink

After 5 years of ‘Gap Eul Byeongbang,’ my body has become thinner

Don't ask about harmony, only a round timber stands close

Arirang Arirang Arari appeared

Hand me over to Arirang Ridge

Arirang Arirang Arariyo at the blind end

It's Nobori Ridge, and the coal is flowing easily

Coal-mining town ridge is a maze ridge with no exit

I'm going now

There’s a long way to go even if I shoulder a bundle

If you don't have debt, you'll make money

If you have a healthy body, you will make money

I came here because of my children, did I come here to live alone?

My son shouldn't be a miner, and my daughter shouldn't be a miner either

The company house is like a chicken coop, but in my dreams, it’s a palace

I catch two pigeons with one bean in every 19 holes

I built up this country with the coal that I mined

Arirang Arirang Arari appeared

Hand me over to Arirang Ridge.

Introducing the exhibition

Our Brilliant ‘Coal Age’

Joint exhibition with the region <Coal Age> 2024.4.26.~9.22.

Curator Lee Do-won, Exhibition Management Department

The National Museum of Korean Contemporary History is holding the joint exhibition <Coal Age> with the coal museums in Mungyeong, Boryeong, and Taebaek. When the Dogye mining office in Samcheok closes in 2025, the coal industry, which was the driving force of Korea's industrial development and fuel for the common people, will now become history. We talked with Lee Do-won, a curator in the Exhibition Management Department, about the kind of story contained in the exhibition, which captures Korea’s passionate and hot ‘coal age.’

Q: I’m curious about the starting point of Korea’s coal industry.

Lee Do-won: There is a song called ‘Samtan song’. It shows the era in which the sovereignty of coal mines was regained after liberation. The exact production time is uncertain, but it is known to have been produced in 1946, judging from the contents of the Samcheok Coal Mine Field Report. In the lyrics, words such as ‘our coal mine,’ which contains a sense of ownership over the coal mines, and ‘new country power,’ which means a dream of a future that will be achieved through increased coal production, stand out. You can see how important coal was at the time, and how much pride the coal miners had in their work.

Q: In the past, industrial facilities also used coal as an energy source, right?

Lee Do-won: Yes, that's right. The coal industry not only played an important role in the growth of the industrial economy as a national key industry, but also played a major role in preventing foreign currency outflow by replacing resource imports. The slogan representing the times at the time was ‘Jeungsanbokuk (增産報國),’ which meant repaying the country by increasing coal production.

Q: I think it will be a good opportunity to read our modern history through the medium of ‘coal.’ Could you introduce representative exhibition materials?

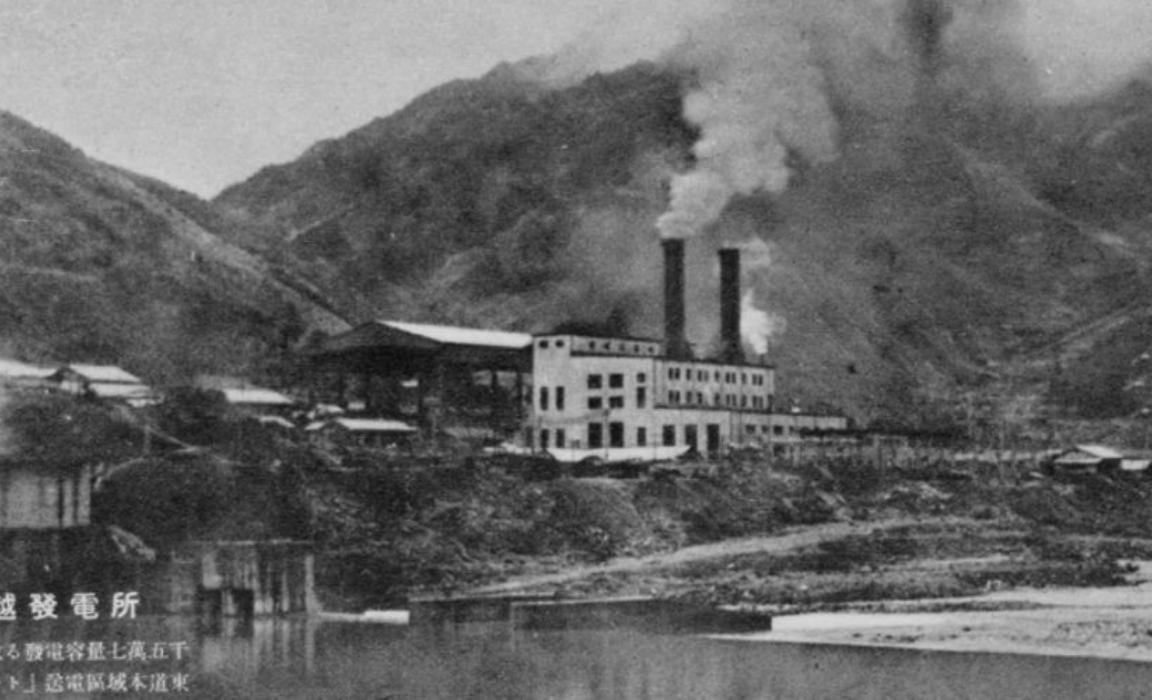

Lee Do-won: In this exhibition, you can enjoy representative materials from three coal museums (Mungyeong, Boryeong, and Taebaek). From the entrance to the exhibition hall, there is a huge lump of coal that attracts everyone's attention. Additionally, the Taebaek area is known as the place where coal was first discovered in South Korea, and the coal in that area was created during the Carboniferous Period of the Paleozoic Era. The process of drilling a tunnel prior to mining coal buried deep underground is called drifting, and what remains representing this drifting process is called ‘jack-hammer’. The jack-hammer owned by the Boryeong Coal Museum will be displayed in its original form, as large as its height, and will be presented vividly. Additionally, you can see various working tools related to coal and coal mining.

Q: Could you please introduce the other exhibition materials that should be viewed meaningful?

Lee Do-won: At that time, there was a motto hanging at the entrance to the tunnel that read, “Dad! Stay safe today.” The work site was so dangerous. To ensure the safety of the miners, protecting their head and spine is a top priority. There is always a risk of pumice or lump coal falling in a coal mine. Back supports are essential safety protective equipment that protect miners from shock and reduce the risk of injury. In this exhibition, you can see the spine protectors used at the Mungyeong mining office. You can see the painting <Coalman II> (1985) by Hwang Jae-hyung, known as the ‘miner painter.’

Q: What does a coal picker do?

Lee Do-won: Coal pickers are those who pick out impurities from mined coal. It is easy to think of coal mines as the domain of male workers, but coal picking was the domain of female workers. It is said that the competition among coal pickers is stiff due to high compensation, and there are few jobs for women in coal mining areas. Coal mines also provided priority employment opportunities to women whose husbands or family members were injured or died in coal mines to make a living.

Q: What message do you want to give to visitors through this exhibition?

Lee Do-won: The era of coal, the fuel for the common people and the engine of growth, is coming to an end. The 347 coal mines that produced 24.3 million tons in 1988 have gradually disappeared due to the coal industry rationalization policy, and are now a part of history. In 2025, with the closure of the last coal mine under the Korea Coal Corporation, there will be only one privately owned coal mine left in South Korea. I hope that visitors can encounter these people in the coal mining area at the time through the various exhibition artifacts, and I hope this will be a good opportunity to think about how we should remember and preserve the legacy of the coal industry in the future.

Be in harmony Post

How do Japanese people feel about Koreans’ emotional expressions in Korean cultural content?

Aya Narikawa Freelance writer,

CEO of Momo Culture Bridge Co., Ltd.

Recently, Korean cultural content has been gaining massive popularity in Japan.

However, Japanese people sometimes have questions while watching some scenes, as there are differences between the Korean and Japanese cultures.

There are quite a few Japanese people who particularly have questions on Koreans' emotional expressions.

Korean Wave at the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History

Last March, I visited the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History with 22 students from Nagoya University of the Arts. This is the first time that students from Nagoya University of the Arts, who originally went to the United States for training, has come to Korea. The reason for the change in travel destination is not only that travel to the United States has become more expensive due to the low yen phenomenon, but also students' interest in Korean culture has increased.

I led the interpretation and explanation of the history gallery on the 5th floor. The history gallery is a permanent exhibition hall that introduces modern and contemporary Korean history. The students were planning to go to Imjingak in Paju the next day, so they wanted to learn more about the Korean War and the division of North and South Korea in advance. However, the students' faces lit up when they entered the Korean Wave exhibition corner. Many students showed deep interest, including students who said they learned Korean because they liked K-pop and Korean dramas. In the ‘financial crisis viewed through popular culture’ section, there were posters for the movie <Default> and the drama <Incomplete Life>. The exhibition commentary continued to tackle issues, such as employment difficulties and the increase in irregular workers, following the financial crisis, and Japanese students who were born and grew up during the economic downturn after the bubble burst would have had plenty to sympathize with.

Such different expressions of emotion in Korea and Japan

After working as a reporter for 『The Asahi Shimbun』 for nine years, I left the company in 2017 and went to Korea. I sometimes do interpretation work, but my main job is writing about Korean movies and dramas for Japanese readers. Last year, I published a book called 『 Why Local Korean Movies and Dramas? (現地発 韓国映画・ドラマのなぜ?)』 in Japan. Immediately after the success of director Bong Joon-ho's film "Parasite" in 2020, the number of people watching Korean movies and dramas on Netflix increased rapidly in Japan, as people spent more time at home due to the impact of COVID-19. This is called the 4th Korean Wave boom. However, Japanese people sometimes have questions while watching some scenes, as there are differences between Korean and Japanese cultures. There are quite a few Japanese people who particularly have questions about Koreans' emotional expressions. For example, in Korea, people say 'a pain in the neck’ when they are angry or shocked, but Japanese people are not familiar with that expression. Moreover, there are many scenes expressing anger in Korean movies and dramas, and the expressions are diverse: spraying water on the face, slapping with kimchi, hair-pulling fight, etc. These are unfamiliar expressions to Japanese people. The drama <Eye Love You>, which has recently become a hot topic in Japan, tells the love story of a Japanese woman, Yuri, and a Korean student, Tae-o. As the main characters are a Korean man and a Japanese woman, cultural differences between the two countries are often seen. For example, there is a scene where Tae-o does not know the meaning of the Japanese word ‘kyosukudesu (恐縮です),’ and asks his senior what it means. When his senior responds, “It means ‘I’m sorry or thank you,’” Tae-o asks with an uncomprehending look, “Which of the two does it mean?” In fact, in Japan, ‘sumimasen (すみません)’ is used much more than ‘kyosukudesu,’ which also contains both the meaning of ‘sorry’ and ‘thank you.’ When you receive a gift and say “sumimasen,” it basically means that you are grateful, but it also means that you are sorry for making them spend time and money on you. This comes from the Japanese attitude of being conscious and considerate of others

When I first came to Korea, I habitually said “I’m sorry” to people who did something for me. Most Koreans then looked puzzled and said, “What are you sorry about?” Korean people express their emotions more clearly than Japanese people. Things to be grateful for are things to be grateful for, things to be sorry for are things to be sorry about. The expression ‘I love you,’ which Koreans often use, is also unfamiliar to Japanese people. A scene where a mother and son talk on the phone and say to each other, “Son, I love you” and “Mom, I love you,” is something that cannot happen in Japan. The Japanese word ‘Aishiteru (愛してる),’ which means ‘I love you,’ is not often used even between lovers or married couples. I also find it awkward to express myself verbally and to listen to them. To me, showing it through actions feels more sincere.

To state the obvious, emotional expressions in Korean movies and dramas are often more exaggerated than in real life. This is probably done to make them easier to convey to audiences and viewers. The absorbing power and sense of speed based on strong emotional expressions may be one of the reasons for the popularity of Korean cultural content. In Japanese works, ‘silence’ is often used when angry, but this mild expression of emotion would not be appealing to Koreans.

Aya Narikawa (成川彩)

After working as a reporter for 『The Asahi Shimbun』 for nine years, he is currently working as a freelance writer. He writes for media outlets in both Korea and Japan, including 『Korea JoongAng Daily』 and 『Kyodo News』, and published 『No Matter Where I am, I am Myself』 in Korea in 2020, and 『Why Local Korean Movies and Dramas?』 in Japan in 2023. In 2023, he won the grand prize in the media category at the Hakbong Awards.

Museum Story

Review 01

Curator Lee Ji-hye, Exhibition Management Department

A special photo exhibition commemorating the 140th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Korea and Italy

All Roads Lead to History: Italy and Korea

This year marks the 140th anniversary of Italy–Korea ties. The photo exhibition, <All Roads Lead to History: Italy and Korea>, which opened on Monday, February 26, 2024, highlights the relationship between Korea and Italy in our modern history. Italy has maintained friendly relations with Korea for over 140 years. After the Italian-Korean Treaty of 1884, the two countries began full-scale diplomatic negotiations, shared the pain of the Korean War, and developed a deeply ‘communicative’ relationship through exchanges in various fields.

This exhibition consists of four parts, and presents photos showing the history of exchange between Korea and Italy, ranging from sports, science, classical music, to popular music: Photos taken by Carlo Rossetti, the Italian consul in Korea; photos and videos showing the 68th Red Cross Hospital, which stayed in Korea from 1951 to 1955 and provided relief; and the process by which the consulates of both countries were promoted to embassies until today. Furthermore, a video was produced showing the scenery of Korea and Italy reflecting each other’s history across the rippling sea to show that the two peninsula countries have created their own history while influencing each other. The video room has mirrors on three sides, and the background music is relatively familiar to Koreans: a canzone ‘Come back to Sorrento,’ and Puccini’s opera aria ‘O mio babbino caro (Oh my beloved father).’ The intention is for this music to be played throughout the exhibition hall so that visitors can enjoy the exhibition along with Italian music.

An important aspects of organizing this exhibition was identifying the points of contact between the histories of Korea and Italy. World-renowned Italian automobile designer Giorgetto Giugiaro designed Korea’s first unique model car, the ‘Pony,’ and famous Italian composer Giorgio Moroder composed the theme song ‘Hand in Hand’ for the 1988 Seoul Olympics. The opera performance based on the theme of ‘Pinocchio,’ the main character in the novel written by a Florentine writer, and Dante’s Divine Comedy, which is deeply inspirational in today’s popular culture, were also highlighted, as their relationship with Italy is not well known although they are familiar to us.

This photo exhibition, co-hosted by the Embassy of Italy in Korea, the Italian Cultural Institute of Seoul, Yonhap News Agency, and the Italian ANSA news agency, was made possible through the active cooperation of each organization. To strengthen the meaning of the 140th anniversary of Italy–Korea ties, Italian was included in both photo captions and panels. This year and next year will also be the year of cultural exchange between Korea and Italy. This exhibition was very meaningful as it was not only the first opening of 2024 for our museum, but also the first event at the Embassy of Italy to commemorate the 140th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries. We hope that this exhibition will be an opportunity for visitors to gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between Korea and Italy.

Review 02

Curator Hong Yeon-ju, Education Department

Children, come to the Interacive Gallery!

The Children's Museum, located on the first floor of the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History, will be merged with the experience center on the fourth floor in the first half of this year. The Children's Museum opened as <Our History Treasure House> on December 27, 2012, and was reorganized into a space that focused on experiential exhibitions as <Our History Dream Village> on December 28, 2016. It has served as a venue where children could learn and experience a variety of exhibitions related to modern and contemporary history.

For about 10 years, the Children's Museum has been loved by many visitors. It was a space that children of various ages, from infants to children under 13, visited and spent their time. As the number of child visitors increased and children of various ages visited, the museum needed to provide richer experiential exhibition content in a wider space.

After careful consideration, the Children's Museum integrated the children's experience exhibition space into the 4th floor experience hall. There, many child visitors will be able to enjoy experiential exhibitions in a larger space. The goal is to provide a venue for children of various ages to communicate and talk with their families while encountering diverse contents of our modern history.

The Children's Museum on the first floor will be open until March 31st, and will undergo remodeling for a month, beginning in April. The space that was previously a children's museum will be transformed into a multi-purpose facility where visitors can spend their time more comfortably.

Review 03

Educational and cultural events commemorating March 1st

To celebrate the 105th anniversary of the March 1st Movement, the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History held many events where people could hear, touch, and experience the movement together. On February 27th, Professor Kim Jeong-in (Chuncheon National University of Education) gave a special lecture in the museum classroom on the topic of ‘The March 1st Movement and Democracy’, and on the 29th, Professor Jeong Byeong-wook (Research Institute of Korean Studies, Korea University) gave a special lecture in the museum classroom on the topic ‘The March 1st Movement of the Unknowns’. The cultural event, ‘‘So am I a March 1st activist,’ was held in the 1st floor lobby and in the 3rd floor multipurpose hall, which included various experiential activities allowing children and families to reflect on the historical significance of the March 1st Movement. The participants engraved the meaning of the March 1st Movement in their hearts through different activities, such as fixing nails to a wooden board and winding thread to make the national flag, playing a memory game that matches the portrait cards of independence activists of the March 1st Movement with event cards, printing the Declaration of Independence, and playing a game of solving the code in the Declaration of Independence, etc. In the classroom, education was provided for children and families under the theme of ‘Exploring the March 1st Movement at the Museum.’ The participants had a meaningful time learning about the background and meaning of the March 1st Movement through the said exhibits, and engaged in crafting experiences.

Review 04

The story of ‘Blue House,’ a major space in modern and contemporary Korean history And the four seasons with music

The National Museum of Korean Contemporary History carries out a project to discover historical and cultural values in major modern and contemporary spaces. In the first project, a total of three types of materials have been released on the museum website (Research Publications>Publications) and the museum's official YouTube account: 1 historical culture book and 1 video titled 《Under Baegak Mountain, the Story of the Blue House》 covering the historical background of the Blue House, and 1 video titled 《The Four Seasons pervading on Blue Roof Tiles》, produced in the form of a playlist (music playlist), showing the changes in the scenery of the Blue House throughout the four seasons. The historical culture book 《Under Baegak Mountain, the Story of the Blue House》 is a popular book that shares the historical story of the Blue House from the Goryeo Dynasty to the present. The main contents of the book have also been produced in an 18-minute video. 《The Four Seasons pervading on Blue Roof Tiles》 organizes the changes in the Blue House scenery in the form of a music playlist, allowing you to enjoy the space of the Blue House in the video as if you were comfortably taking a walk, along with sounds that harmonize with the seasons, such as the sound of the wind, rain, and stepping on fallen leaves.

Review 05

The National Museum of Korean Contemporary History signed a business agreement (MOU) with local institutions

The National Museum of Korean Contemporary History (Director Han Soo) signed a business agreement for exchange, cooperation, and mutual development with local cultural institutions related to modern and contemporary history. The main business agreements include: 1) joint development and utilization of content, 2) conducting research related to modern and contemporary history, 3) holding joint exhibitions, and 4) human exchange and joint establishment of domestic and international networks, etc. On January 30, a business agreement was signed with the Presidential Archives (Director Lee Dong-hyeok) to comprehensively and systematically carry out various projects related to the development, exhibition, and research of joint content by using materials on the modern and contemporary history of the Republic of Korea and its past presidents.

Subsequently, on February 27, a business agreement was signed with Pocheon City (Mayor Baek Young-hyeon) to enable the two organizations to cooperate and provide advice on the construction of the Pocheon City Museum. On March 22, a tripartite business agreement was signed between the Seoul Museum of History and the Chungnam Institute of History and Culture. And, on March 28, a business agreement was signed with Jinju City to promote business discussions related to the construction of the Jinju History Hall. “This business agreement will provide an important opportunity to strengthen the investigation and research functions of each organization, and to present diverse and interesting content to the public,” said Director Han Soo.

Preview 01

Gwanghwamun historical walk with 4 experts

The citizen lecture on modern history in the first half of 2024 is a field survey program called ‘History Walk’ that tours modern and contemporary historical sites around Gwanghwamun from April to May. The program is designed to allow people to interpret the space of Gwanghwamun from various perspectives, and consists of lectures and field trips led by experts. You can check the program contents and apply for training on the museum website.

Much Toon

National Museum of Korean Contemporary History Newsletter 2024 Spring (Vol. 72) / ISSN 2384-230X

198 Sejong-daero, Jongro-gu, Seoul, 03141, Republic of Korea / 82-2-3703-9200 / www.much.go.kr

Editor:Ahn SeongIn, Kim YangJeong, Jeong Suwoon

/ Design: plus81studios

Copyright. National Museum of Korean Contemporary History all rights reserved.