2024 Autumn Vol.74

Introducing the Exhibition

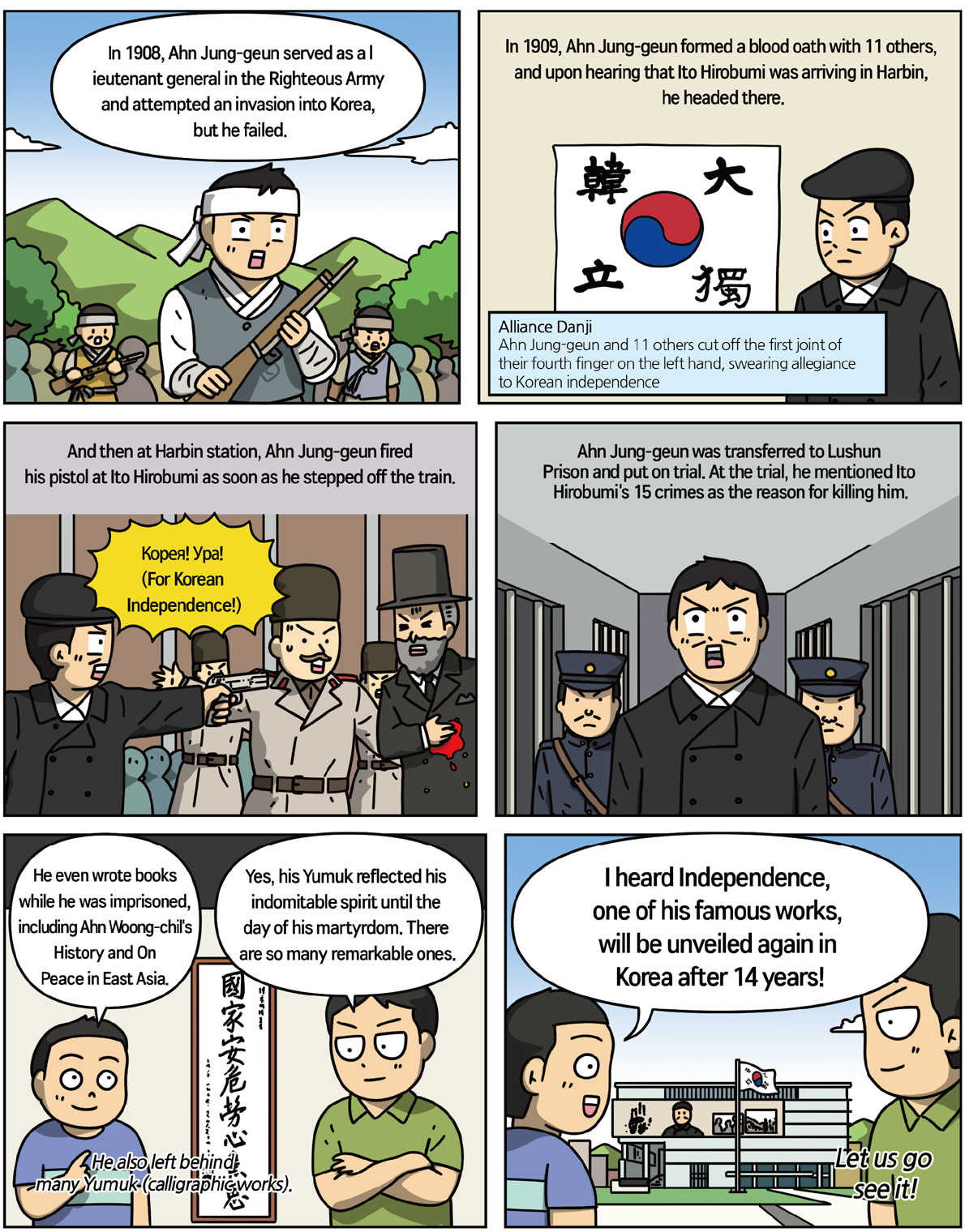

The Ideology of Ahn Jung-geun through his Calligraphy

A Special Exhibition in Commemoration of Patriot Ahn Jung-geun’s Harbin Righteous Deed<Ahn Jung-geun's Calligraphy>

October 24, 2024 – March 31, 2025

The National Museum of Korean Contemporary History, in collaboration with the Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Society and the Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Hall, is hosting a special exhibition to commemorate Ahn Jung-geun's Harbin Righteous Deed. The special exhibition will be held on Friday, October 24, 2024, until Monday, March 31, 2025, at the museum's third-floor exhibition hall.

The National Museum of Korean Contemporary History, in partnership with the Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Society and the Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Hall, proudly presents the special exhibition <Ahn Jung-geun's Calligraphy>, in commemoration of Ahn Jung-geun's Harbin Righteous Deed (1909.10.26) and his martyrdom (1910.3.26). The exhibition will run from October 24, 2024, to March 31, 2025, on the third floor of the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History.

The exhibition focuses on the calligraphy works left behind by Ahn Jung-geun, known as yumuk (遺墨, posthumous writings). These calligraphies have been written between February and March 1910, when his execution was announced until the day it was carried out. Ahn's writing was powerful and full of spirit, amid his imminent death, and was loved by many people in Korea, China, and Japan. His calligraphy contains his spirit, such as his will for independence, his idea of East Asian peace, and his values. The power and vigor in Ahn’s writing continues to inspire admiration across East Asia. Through the works displayed in this exhibition, visitors can learn so much from his life, philosophy, and unwavering determination.

Ahn Jung-geun's Calligraphy, Ahn Jung-geun's Life

This special exhibition offers a rare opportunity to view 19 pieces of Ahn Jung-geun's yumuk, many of which have been scattered in Korea and abroad, and are not easily accessible. Notably, it will be a more meaningful event as four pieces from Ryukoku University in Japan will be exhibited again in Korea after 14 years.

These works include pieces such as 獨立 (Independence), 戒愼乎其所不睹 (Be cautious and discreet in what no one sees)1), 敏而好學 不恥下問 (Be eager to learn and do not be ashamed to ask your subordinates)2), and 不仁者 不可以久處約 (An unkind person cannot endure hardship for long)3). Moreover, 15 pieces of yumuk that remain in Korea will also be on display. These include works that reflect Ahn’s identity as a patriot, such as 國家安危 勞心焦思 (Worry for the nation’s safety and devote one’s mind)4) and 爲國獻身 軍人本分 (It is the duty of a soldier to sacrifice oneself for the country.)5). There will also be works that embody Ahn’s philosophy of East Asian peace, such as 東洋大勢思杳玄 有志男兒豈安眠 和局未成猶慷慨 政略不改眞可憐 (The situation in East Asia seems obscure; how can a man of ambition rest easily? I lament that peace has not been achieved and that wars of aggression remain unchanged)6), as well as those that express his spirit and values, like 丈夫雖死心如鐵 義士臨危氣似雲 (Though a man dies, his spirit remains steadfast as iron; though a righteous man faces danger, his courage rises like clouds)7) and 黃金百萬兩 不如一敎子 (A million ounces of gold cannot compare to teaching a single child)8).

Footnotes:1) Be cautious and be discreet in what no one sees.

2) Be eager to learn and do not be ashamed to ask your subordinates.

3) An unkind person cannot endure hardship for long.

4) Worry for the nation’s safety and devote one’s mind.

5) It is the duty of a soldier to sacrifice oneself for the country.

6) The situation in East Asia seems obscure; how can a man of ambition rest easily? I lament that peace has not been achieved, and that wars of aggression remain unchanged.

7) Though a man dies, his spirit remains steadfast as iron; though a righteous man faces danger, his courage rises like clouds.

8) A million ounces of gold cannot compare to teaching a child.

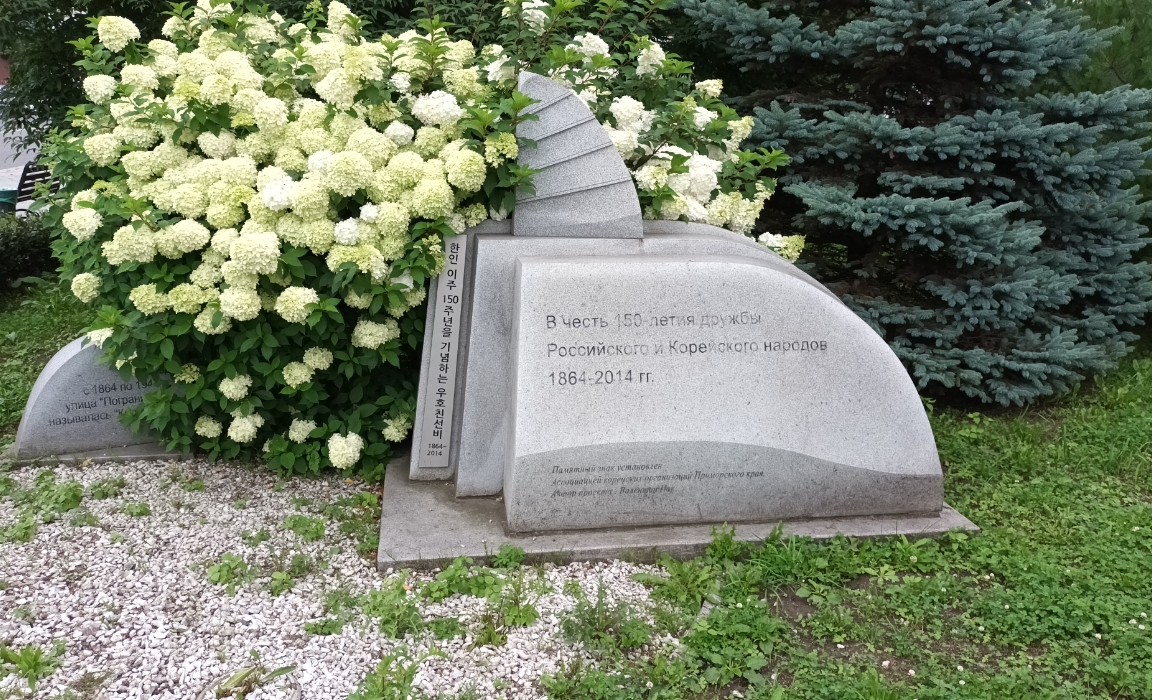

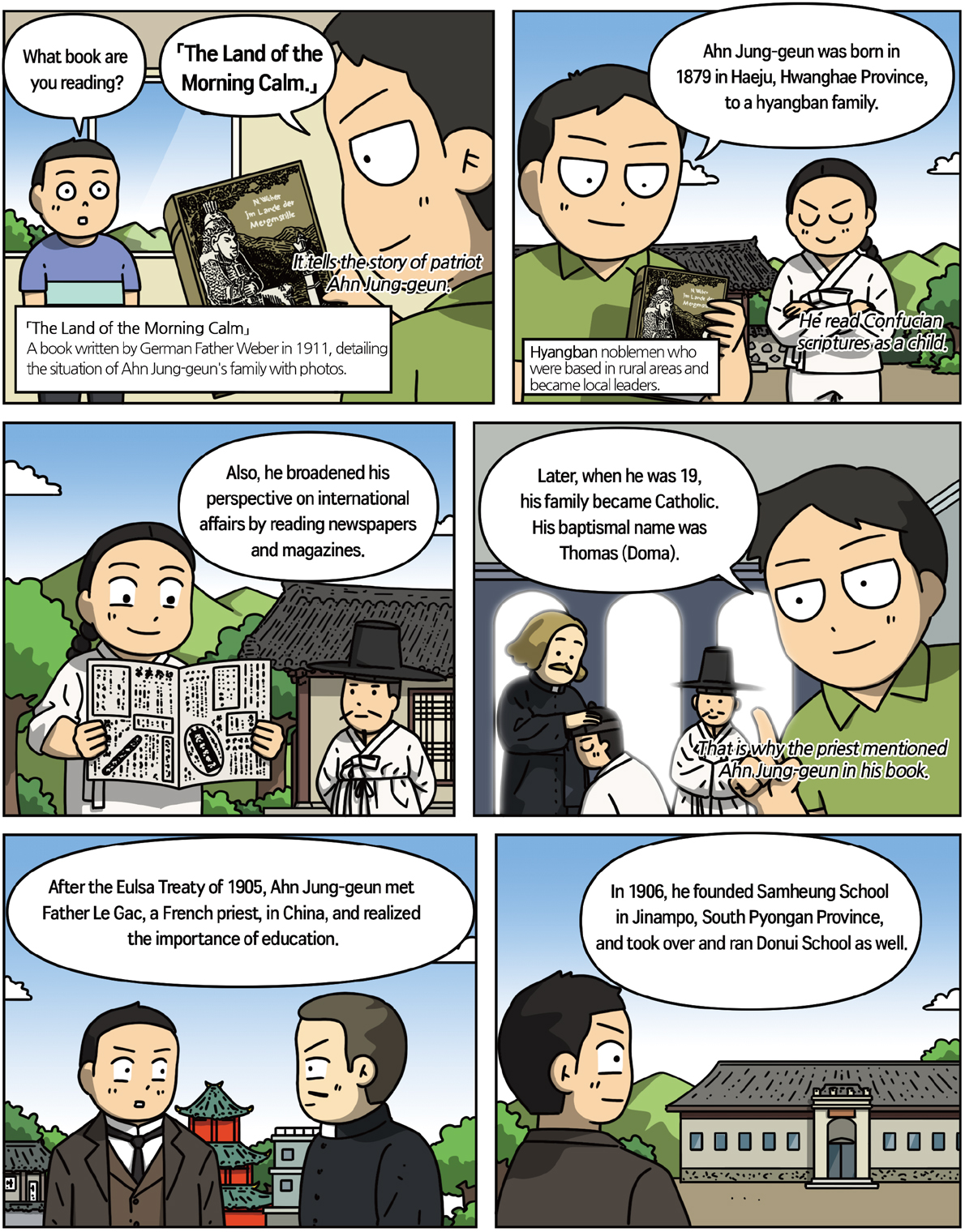

The special exhibition is composed of seven themes inspired by his childhood name, Ahn Eung-chil (安應七), and is centered on the calligraphies of Ahn Jung-geun. The themes include his family’s history as patriots, his early years, his conversion to Catholicism and related activities that changed his life, Ahn's patriotic enlightenment activities, his participation in anti-Japanese resistance in the Russian Far East, the secret society he formed with comrades like Woo Deok-soon, Cho Do-sun, and Yoo Dong-ha, Harbin Righteous Deed and his vision of East Asian peace, his legal struggles while imprisoned in Lushun, and his ultimate martyrdom.

Remembering Ahn Jung-geun's Righteous Deeds and Thoughts

When people think of Ahn Jung-geun, they often only think of the Harbin Righteous Deed. However, Ahn Jung-geun was a philosopher, a writer, and a righteous man who constantly grew with the times. The National Museum of Korean Contemporary History hopes that this exhibition will help visitors discover the many facets of Ahn Jung-geun’s life and reflect on his life, thoughts, and spirit.

Following the Breath of Ahn Jung-geun:

Walking the Path of Independence and Peace

Written by | Kim Wol-bae, Harbin Institute of Technology

This article explores overseas historical sites associated with Ahn Jung-geun. You can find traces of Ahn Jung-geun in China’s Shandong Peninsula, Shanghai, Harbin, and Vladivostok, Russia. The path to Korean independence through the Harbin Righteous Deed was a bullet of justice, while his writing of the Theory of Peace in the East in Lushun was his pen for peace.

Harbin remains on the path to Korean independence

Корея! Ура!

Harbin (哈爾濱) is known as ‘a small fishing village where nets are dried’ in Manchurian. It is a place that Koreans want to visit the most.

Harbin has traces of the ‘Ten Days of Ahn Jung-geun (October 22, 1909 - November 1, 1909)’. There are several historical sites linked to Ahn Jung-geun, including Kim Seong-baek’s house in the Daoli district’s Senlin Street, which was the command center of the Harbin Righteous Deed; the Harbin Park (now Zhaolin Park), where Ahn expressed his wish to be temporarily buried after his death and where he strengthened his resolve; Dongxing School (now Daoli Central Primary School), where Ahn was introduced to his assistant, Cho Do-seon; Harbin Station’s southern plaza, where he made the will for Korean independence known to the world; and the Japanese consulate in Harbin (now Huayuan Primary School), where Ahn was imprisoned after the Righteous Deed. These are just a few of the many significant sites related to Ahn Jung-geun in Harbin.

The Memorial Monument at Harbin Park

If you enter through the south gate of Harbin Park (now Zhaolin Park), you will find the memorial monument engraved with Ahn Jung-geun’s calligraphy.

On March 11, 1910, Ahn Jung-geun left a final request with Father Wilhelm and his brothers, Ahn Jeong-geun and Ahn Gong-geun, saying, “If I die, bury my bones in Harbin Park, and when our country is restored, return (返葬)1) them to my homeland.” The current name of Harbin Park is Zhaolin Park. It was built in 1906, but, in 1963, it was renamed Zhaolin Park after the Chinese anti-Japanese activist General Li Zhaolin (李兆麟, 1910-1946) was buried there. In the park, a memorial monument with Ahn’s calligraphy stands, reflecting his spirit and ideals. On the morning of October 23, 1909, the day after his arrival in Harbin, Ahn visited a barbershop with his comrades Woo Deok-soon and Ryu Dong-ha, and they took a commemorative photo at a nearby studio. The following day, Ahn and Woo strolled through Harbin Park, reviewing their plans for the Righteous Deed. That evening, Ahn wrote Song of the Righteous Man (丈夫歌).

1) Moving a person who died in a foreign land to his or her hometown or place of residence and burying him or her thereIn 2007, the Chinese government displayed Ahn Jung-geun’s phrase, “青草塘” (Cheongchodang), and a photo of Ahn Jung-geun on a signboard. A short walk to the left of the signboard leads to a pond and a pavilion, where the monument of Ahn Jung-geun, a hero of the Korean independence movement, stood proudly and welcomed the people at the park with a dignified and resolute posture. The monument features Ahn’s handprint, the inscription “靑草塘” from Ahn’s calligraphy, his name, “安重根,” and the impression of the left hand with which he took the oath of the “Cut Finger Alliance.”

The Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Hall at Harbin Station, a Symbol of Korea-China Friendship

Ahn Jung-geun assassinated Ito Hirobumi, who was at the forefront of the invasion of the Korean Empire, on October 26, 1909, at Harbin Station. This act was not a personal one but carried out in his role as the Deputy General of the Korean Army, thus eliminating an enemy general while carrying out the war of independence as a lieutenant general of the Korean volunteer army. It was a just punishment to protect human freedom against the destroyer of peace in the East. The Harbin Righteous Deed revealed Japan’s aggressive ambitions and crimes, while Ahn’s actions served to publicize Korea’s determination to fight for independence.

The Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Hall was first established on July 1, 2006, at the Joseon National Art Museum, and was officially opened at Harbin Station on January 19, 2014. It was temporarily moved back to the Joseon National Art Museum due to the reconstruction of Harbin Station, and reopened at the South Plaza of Harbin Station on March 30, 2019. It features Ahn Jung-geun’s birth, activities, martyrdom, and evaluation. You can see the Harbin Righteous Deed site through the glass walls installed in this memorial hall. The memorial hall has an area of 488 ㎡, and at the entrance, a statue of Ahn Jung-geun is seen stepping on the Korean Peninsula and holding a copy of the Eastern Peace Theory. The clock in the hall is set to 9:30, the time of the Harbin Righteous Deed. The relief of the statue expresses Ahn Jung-geun’s thoughts in the form of Hangul, the Korean alphabet.

The Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Hall at Harbin Station, a Symbol of Korea-China Friendship

Lushun, located at the southern tip of the Liaodong Peninsula, is full of the scars of modern Chinese history due to the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars. It is a place of significance for modern Chinese history as well as the history of East Asia. It is a textbook of sorrow, ambition, and historical sites covering the modern history of Korea, China, Russia, and Japan.

Key sites in Lushun include the Kwantung Court, where Ahn defended the legitimacy of his actions during his trial; the Kwantung Governor-General’s Prison (now Lushun Russo-Japanese Prison), where Ahn was held for 144 days, during which he wrote over 200 pieces of calligraphy, the History of Ahn Eung-chil, and the unfinished Eastern Peace Theory; and the Yuanbosan area (now Hill-One Apartments), the site of a 2008 joint Korea-China excavation effort to find Ahn’s remains. The Kwantung Governor-General’s Prison housed both Ahn Jung-geun and independence activist Shin Chae-ho. During his 144-day imprisonment, Ahn penned about 200 calligraphy works, wrote the History of Ahn Eung-chil, and began writing the Eastern Peace Theory before his execution. This prison is the largest international prison established by an imperialist power. Its massive size, complete preservation, and rich historical significance make it an uncommon sight in the world. It opened as a museum on July 6, 1970, and it continues to exist to this day.

Stories about modern history

The Current Significance of Ahn Jung-geun's "Eastern Peace Theory"

Written by | Lee Joo-hwa, Curator at the Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Museum

One hundred fifteen years has passed since Ahn Jung-geun assassinated Ito Hirobumi at Harbin Station. Ahn was subjected to an unjust trial, and ended his life in Lushun Prison. The Eastern Peace Theory, written by Ahn Jung-geun before he ended his life in Lushun Prison, still conveys much meaning to us today.

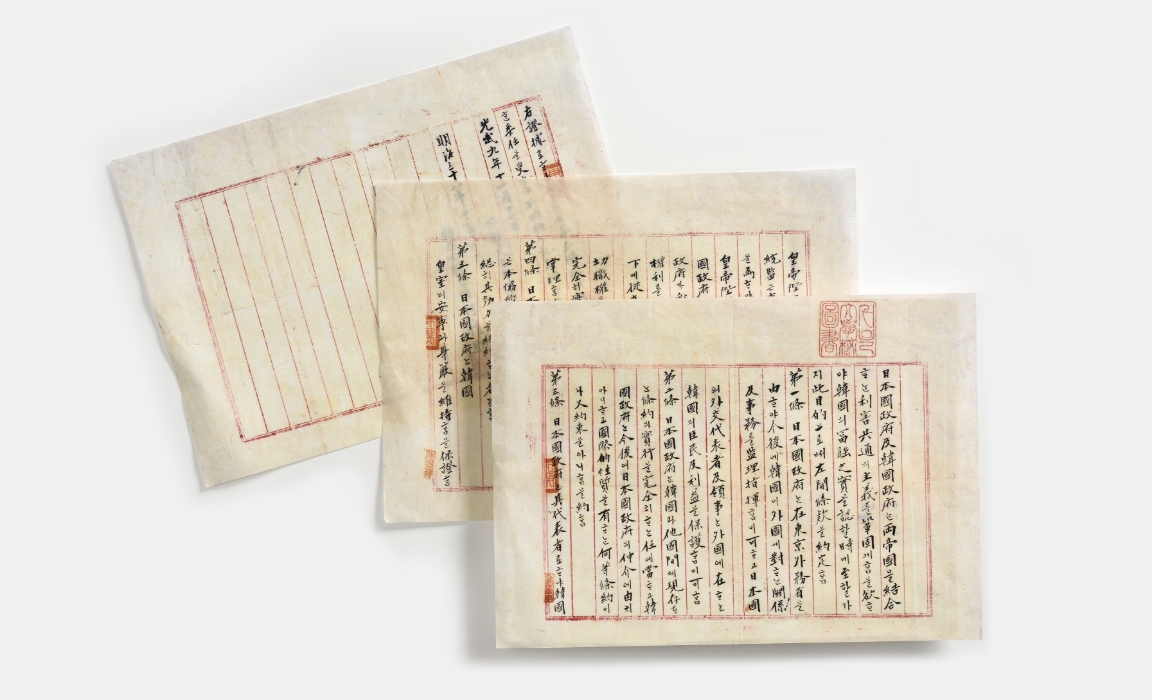

Ahn Jung-geun's Vision for Peace in East Asia

On October 26, 1909, Ahn Jung-geun (安重根, 1879-1910) assassinated Ito Hirobumi (伊藤博文, 1841-1909), the Chairman of the Japanese Privy Council, at Harbin Station in northern Manchuria. Ito served as prime minister four times since becoming the first prime minister of Japan after the Meiji Restoration, serving four terms in total. He also played a pivotal role in Korea's forced annexation, having served as the first resident-general of Korea after the Eulsa Treaty of 1905.

After Ahn Jung-geun's assassination, the Japanese denounced Ahn Jung-geun as a "heinous man" for assassinating Ito, who was the drafter of the Meiji Constitution and a politician who led the development of the modern state of Japan. However, Koreans respected Ahn Jung-geun as a "righteous martyr" for eliminating Ito, the man responsible for Korea’s colonization.

Ahn initially believed that the loss of some of Korea's sovereignty, including diplomatic rights, due to the Eulsa Treaty was due to a lack of ability. Therefore, he wanted to contribute to the independence of Korea and peace in the East by informing the world of the aggressive nature of imperialist Japan through armed struggles, such as the activities of the Righteous Army and the execution of Ito, who promoted the Resident-General's politics. This led him to write The Eastern Peace Theory while awaiting his execution in Lushun Prison.

Ahn’s Eastern Peace Theory is composed of five parts: Introduction, Background, Current Situation, Solutions, and a Q&A. However, since Ahn’s execution was carried out sooner than expected, only the Introduction and Background were completed. It does not contain the entirety of the theory that he had envisioned.

Fortunately, however, the record of the interview between Ahn Jung-geun and Hiraishi Ujito, the Chief Justice of the High Court of the Japanese Government-General of Kwantung, on February 17, 1910, contains a specific implementation plan for his ideas. According to this document, Ahn’s vision for a peaceful East Asia involved several concrete proposals:

First, Ahn proposed making Lushun a joint military harbor for Korea, China, and Japan, creating a united military force, and fostering camaraderie between the three nations through foreign language education.

Second, he suggested that representatives from the three nations convene in Lushun to form a peace organization, making Lushun the “foundation of peace.” It was a significant proposal, as Lushun was a disputed area occupied by Japan at the time.

Third, he proposed establishing a shared bank funded by the three nations’ recruit members of the ‘Oriental Peace Conference’ and establish a bank with their membership fees, and issue a common currency for each country to facilitate finance. This is a claim that Korea, China, and Japan should establish a joint banking system for the three countries, and issue a common currency to make the three countries a financial community.

Fourth, he advocated for the modernization of Korea and China through Japan’s guidance, with the goal of mutual economic growth. He emphasized that Korea and China should grow their economies through the cooperation of Japan, which was a pioneer in modernization at the time, and become modern states together.

Fifth, Ahn suggested that the emperors of Korea, China, and Japan visit the Pope together, symbolically affirming their status as independent nations recognized by the world and solidifying lasting peace in East Asia.

In short, Ahn’s Eastern Peace Theory proposed the creation of a "Northeast Asian Union," in which Korea, China, and Japan would cooperate militarily, financially, and economically. Ahn’s vision was for the ‘Northeast Asian Union’ to set an example as a Northeast Asian national community, and expand into an ‘Asian Union’ with the participation of Asian countries such as India, Thailand, Vietnam, and Myanmar.

A Vision of Regional Community Ahead of Its Time

Ahn Jung-geun’s concept of a "Northeast Asian Union" or "Asian Union" in 1910 closely mirrors the formation of the European Union (EU), which was established 82 years later in 1992. In 1993, the Maastricht Treaty came into effect, giving birth to the European Union, a community of European nations. Later, the European Central Bank (ECB), a common bank, was established, the common currency, the Euro, was issued, and Europe began using a single currency in 2002. Since then, the European Union (EU) has contributed to European peace by sharing parliaments, military organizations, universities, banks, and currency.

Ahn’s vision was to establish peace in East Asia, while primarily focused on three Eastern countries of Korea, China, and Japan, or Northeast Asia. In a broad sense, the Orient refers to Asia, including Korea, China, Japan, India, Thailand, Vietnam, and Myanmar. Thus, Ahn’s concept of peace in East Asia implies peace across the entire continent, eventually contributing to global peace.

Moreover, Ahn Jung-geun said, "I killed Ito for Korea and for the world." He also said, "I hoped that Korea and Japan would become closer and more peaceful, and that it would become an example for the five continents. I thought that if I maintained peace in the East and solidified Korea's independence, Korea, China, and Japan would ally and call for peace, and the 80 million or more people would unite and gradually advance toward enlightenment. Furthermore, if I worked for peace with Europe and the countries of the world, the citizens would feel relieved." Thus, his idea of Eastern peace expanded to world peace. In other words, Ahn Jung-geun's Eastern Peace Theory pursued peace in Northeast Asia, peace in Asia, and peace around the world based on the premise of Korea's independence.

Ahn Jung-geun suggested that the three Eastern countries jointly defend against the invasion of Western imperialism, but not to attack the West. He resisted the invasion of Japan and fought an armed struggle, but he did not consider the Japanese people as enemies. Ahn Jung-geun did not kill ‘human Ito’ himself. But as a lieutenant general of the Korean volunteer army, he eliminated the culprit of the invasion for the independence of Korea and peace in the East. Fundamentally, he appeared to espouse Catholic humanism, a peace-loving compatriotism, and a globalist consciousness.

Ahn Jung-geun’s Eastern Peace Theory conveyed the ‘Eastern Strategy’ to Japan, hoping that Japan would become an advanced country that was respected morally, not by force, and a country that supported peace and prosperity in Northeast Asia.

Message of the Eastern Peace Theory to Northeast Asia Today

Today, Korea remains divided, with the North and South militarily opposed under different political systems. China, Japan, and Korea still experience tensions over historical and territorial disputes, while Japan and China vie for dominance in Northeast Asia. The region continues to face high levels of tension, competition, and conflict.

In this context, Ahn Jung-geun’s Eastern Peace Theory and his vision of a "Northeast Asian Union" offer a valuable blueprint to transform this volatile situation into one of lasting peace. If Ahn’s ideals were realized today, they could lead to enduring peace and prosperity in Northeast Asia, and, eventually, peace in Asia and around the world. Ahn Jung-geun’s vision remains relevant even in our time.

About the Author Lee Joo-hwaUniversity. She has worked at the National Folk Museum (Department of Artifact Science) and at the National Museum of Korea (Department of Archaeology and History) before joining the Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Museum as a curator.

Come together

The National Museum of Korean Contemporary History: Singing the national liberation with the National Chorus of Korea

<Korean Independence, Korean People>

Although liberation from Japanese colonial rule and liberation are important historical events in Korea’s modern and contemporary history, as a foreigner, I did not know much about them. I learned the national anthem at a Korean language school, and confidently sang it during my naturalization test, but I can say that I did not know the true meaning of the lyrics.

Stories about Korea’s fight for independence and the sacrifices made along the way can be easily accessed through films like <Assassination> and <The Age of Shadows>, as well as through documentaries, books, and museums. One of the most memorable lines from <Assassination> is, "Even if we fail, we must keep moving forward. Failures accumulate, and with those failures, we move ahead and rise to greater heights." The story of Korea’s independence movement, marked by persistent struggle despite setbacks, and the many independence fighters who emerged during this period captivated me beyond the emotional impact of the film's cinematic mise-en-scène.

However, the only time I felt 'liberation' directly in my daily life was when Koreans cheered enthusiastically at a Korea-Japan match. I had no other opportunity to experience or reflect on the true meaning of Liberation Day.

In 2024, marking the 79th anniversary of Korea’s liberation, I was invited to a Liberation Day commemorative concert hosted by the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History and the National Chorus of Korea. The idea of interpreting a historical event through a cultural performance intrigued me, so I eagerly accepted the invitation.

This concert was a meaningful event, and the performance fully conveyed the joy of liberation and hope for independence that Koreans felt at the time. In <Longing for Geumgangsan>, I thought of my hometown. The scene where I met with an old couple who were shedding tears while listening to <Arirang> still leaves me with a deep emotion. When many voices came together in <National Anthem>, it felt as if the choir members’ singing represented the hearts of independence activists, eliciting a great emotional resonance.

Perhaps this is the power of music, as it can transcend language and cultural barriers.

Even without fully understanding the lyrics, the sheer emotional impact of the music itself was exhilarating. In that moment, I felt a deeper connection to Korea’s independence movement.

The concert left a strong impression on me as a foreigner. Korea's suffering under Japanese occupation and its fight for independence transcended the history of one nation—it was a universal struggle for human freedom and dignity. Korea’s independence movement is not simply the story of a single country, but a symbol of collective effort and sacrifice to protect freedom and rights as humans. I learned through this experience that freedom is not something that is simply given, but something achieved through the sacrifice and dedication of others.

My homeland, Nepal, has plenty of images of a peaceful country, but there was a revolution in Nepal from 1996 to 2006, when there were many people who shed blood for it. Then the monarchy disappeared, and Nepal became a democratic republic. However, is Nepal on the right path toward the future? When thinking about Nepal from the perspective of Korea, which achieved democracy and advanced to the status of a developed nation after its liberation, I cannot help but feel a sense of frustration.

The Nepalese Communist Party (Maoist) sought to end the constitutional monarchy, and established a democratic republic, which led to a civil war from 1996 to 2006. The conflict spread across the nation and resulted in heavy sacrifices. As many as 150,000 people were displaced, and around 7,000 were killed, with 1,700 refugees forced to wander abroad.

Nepal, which had the image of a peaceful country, was at a crossroads of deciding what direction to set for the future while fighting a bloody war. After a series of events, the monarchy was officially abolished in 2007, and Nepal was officially declared a democratic republic in 2008. At first glance, the bloodshed seems to have subsided, but Nepal’s political turmoil remains unresolved. The Nepalese people were fed up with politics. The parliament is dominated by Maoists, and although we are now a republic, nothing has changed in the constitution.

I have never voted in my life. When I was in Nepal, I could not vote because I was young, but now I cannot because there is no overseas absentee voting system.

In that sense, I envied Koreans who expressed their joy of liberation through music. Korea has joined the ranks of advanced countries, and Korean democracy, which seems unstable but still alive with the candlelight of its citizens, seemed amazing.

Liberation Day is not just a day to commemorate a past event; it is a day to remember the hardships endured by many to bring Korea to where it is today, and to express gratitude for their sacrifices. Still, no matter how many times it is emphasized and reflected upon, it is never enough. It’s also a day to remind ourselves of our responsibility to continue protecting this nation's freedom and independence. As a foreigner, I felt the universal values of human dignity and freedom beyond learning about simple historical facts through this event.

Director Martin Scorsese once said, “The most personal is the most creative.” Through the deeply personal experience of attending the Liberation Day concert, I will remember and reflect on the true meaning of Liberation Day in my heart in the most creative way as a foreigner.

Sujan ShakyaSujan Shakya was born and raised in Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal. She studied urban planning at Dankook University and has lived in Korea for 15 years. She participated as a representative of Nepal on JTBC’s Non-Summit from 2014 until its final episode. She currently works at a company related to Korea’s defense industry, while also serving as a member of the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism's Cultural Diversity Committee. Sujan dreams of becoming a representative for immigrants in Korea. She is also involved in translation and public speaking, and is exploring new opportunities.

Museum Story

National Museum of Korean Contemporary History Participates in Seoul Future Heritage Sticker Tour

Seoul conducts an annual sticker tour to encourage citizens' interest and participation in preserving Seoul's Future Heritage. This year, the sticker tour will be held from July 29 to December 31, targeting 25 Seoul future heritage sites. The National Museum of Korean Contemporary History has been selected as the first destination.

The National Museum of Korean Contemporary History is an educational and cultural space that collects, preserves, and studies materials related to the development of Korea, as well as a cultural promotion space that introduces Korea to the world. The museum was selected as a Seoul future heritage site in 2013, recognizing it as an important site for economic and cultural development.

Participants in the sticker tour can collect their tour passports from any of the three designated locations, including the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History. By visiting all 25 Future Heritage sites listed in the passport and collecting stickers at each location, participants can complete their passports.

* Passport collections: Digital Chosun Ilbo (Security Office, 1st floor), Seonyudo Park (Office), and Son Ki-jeong Memorial Hall (Information Desk, 1st floor)

Seoul Future Heritage refers to the tangible and intangible modern and contemporary cultural assets in Seoul that are not registered as national heritage, but are deemed valuable for future generations. These assets are treasures that will be passed on to future generations 100 years from now as common memories or emotions that Seoul citizens have created together in the modern and contemporary times.

Children's Event on National Liberation Day

To commemorate the 79th anniversary of National Liberation Day, the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History hosted educational programs for children and families. The activities included missions where children searched for codes related to Korea's liberation through relics displayed in the museum, and hands-on activities such as making Taegeukgi (Korean national flag) and Mugunghwa (rose of Sharon) pinwheels and Taegeukgi keyrings. These activities helped participants reflect on the historical significance of Korea's liberation.

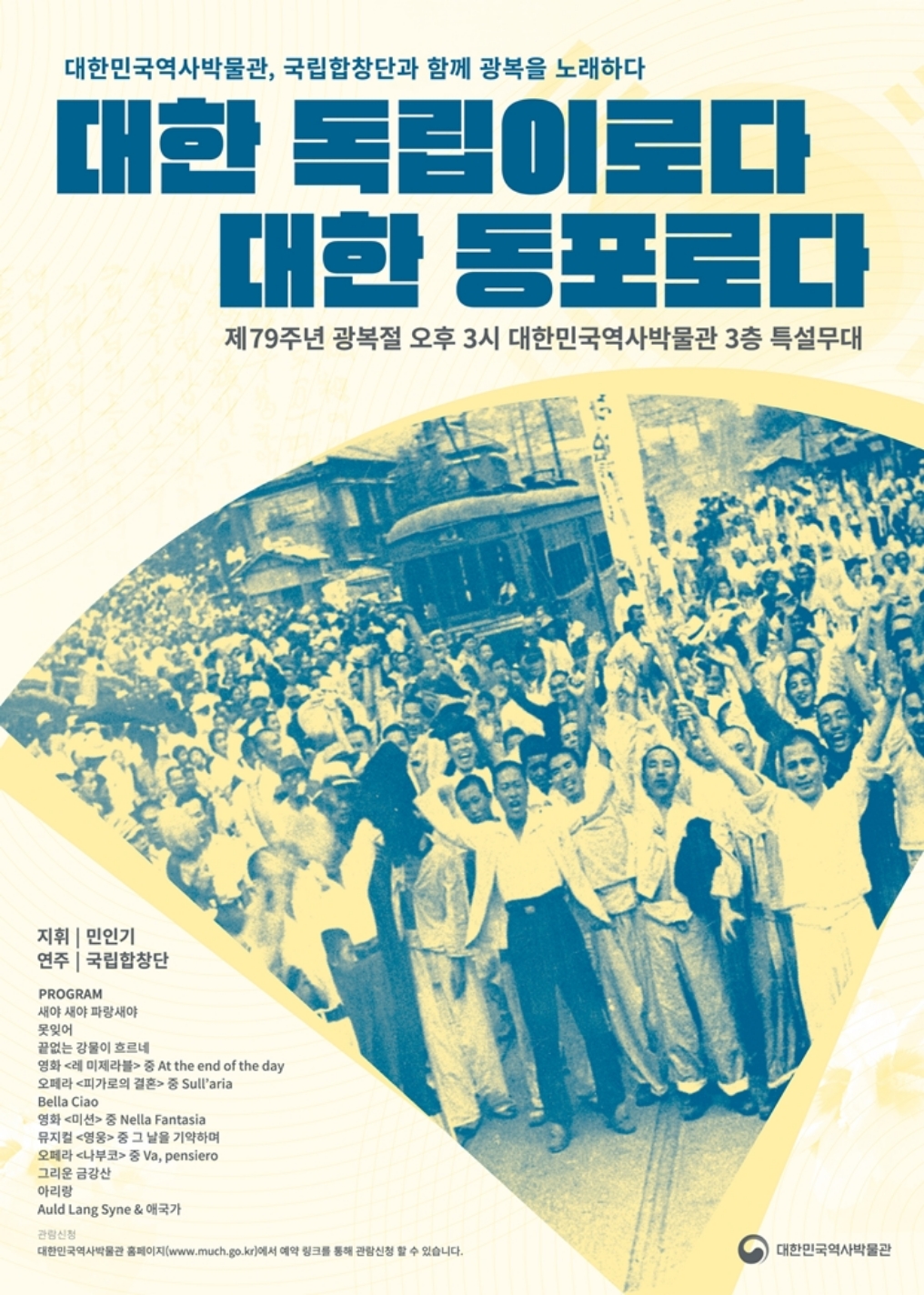

Singing Liberation with the National Chorus: <Korean Independence, Korean People>

In celebration of the 79th anniversary of National Liberation Day, the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History held a performance titled Korean Independence, Korean People at a special stage on the museum's third floor. This performance, along with the National Chorus of Korea (conductor Min In-gi), looked back on the sorrow of losing the country and the struggle for independence, as well as the appearance of those who had to live in that era, through familiar songs. The National Chorus of Korea started with ‘Bird, Bird, Blue Bird,’ and sang ‘That Day, Waiting for’ from the musical Hero and ‘Arirang.’ Their beautiful voices filled the concert hall. Visitors to the museum on Liberation Day packed the performance area, responding with enthusiastic applause.

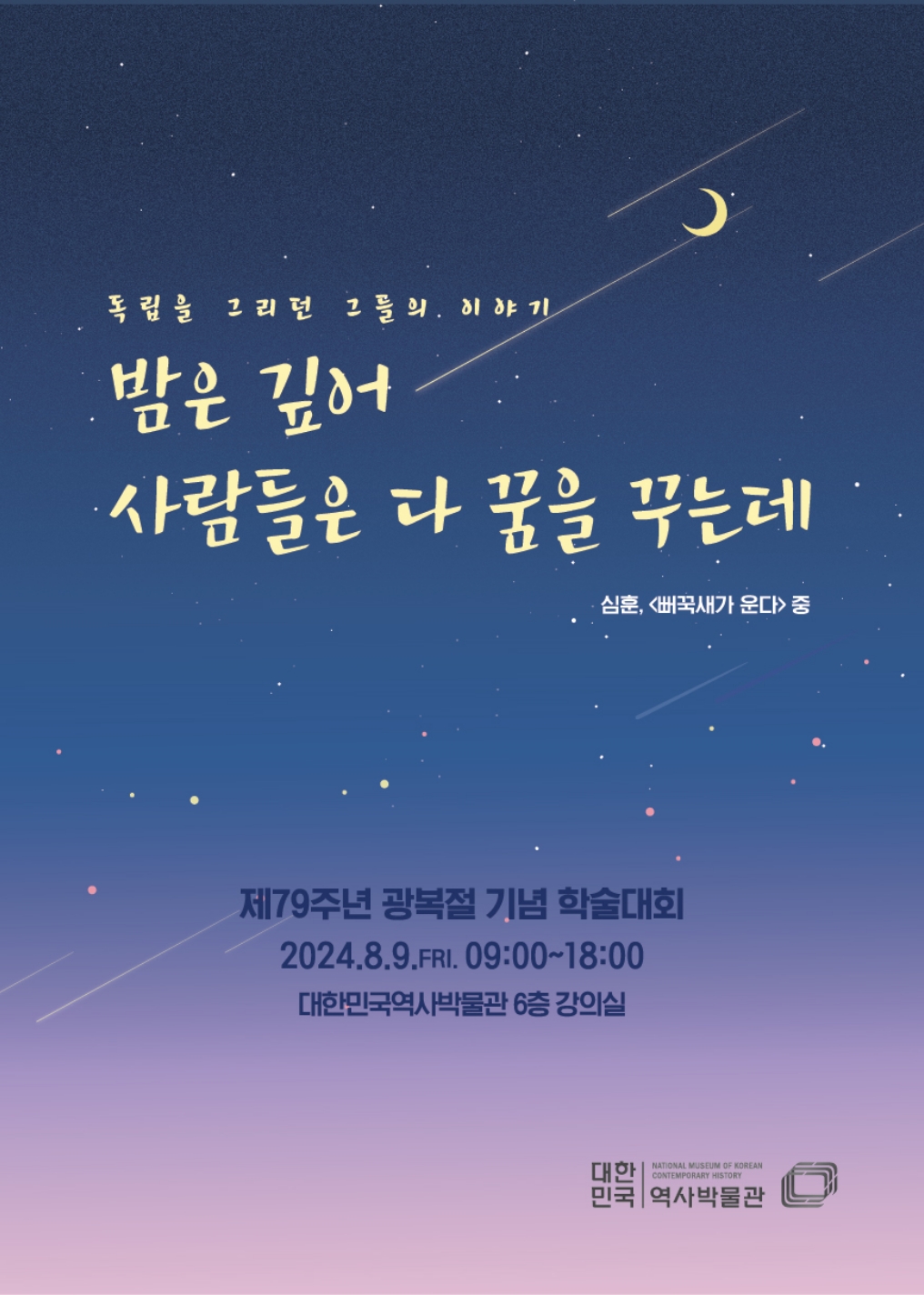

National Liberation Day Academic Conference "The Night is Deep, and Everyone Dreams"

On August 9, the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History hosted an academic conference titled, Stories of Those Who Longed for Independence: The Night is Deep, and Everyone Dreams, to mark the 79th anniversary of National Liberation Day. The title of the conference was inspired by the poem The Cuckoo Cries of poet Shim Hun.

The event featured seven presentations and two performances. The keynote speech, Reading Independence through Culture, of Professor Kim Jung-in of Chuncheon National University of Education was followed by presentations that highlighted the major activities of artists who desired independence in the fields of culture and arts such as literature, music, and theater, as well as the independence movements of ordinary people.

Performances that matched the theme of the academic conference were held before the morning and afternoon presentations. In the morning, vocalist Jang Hye-ryeong performed The Housewife's Righteous Army Movement and A Sorrowful Song, while in the afternoon, violinist Han Un-ji (Busan Symphony Orchestra), granddaughter of anti-Japanese composer Han Hyung-seok, performed Great Korean March and The Amnok River March by using her grandfather’s violin, offering a deeply resonant experience.

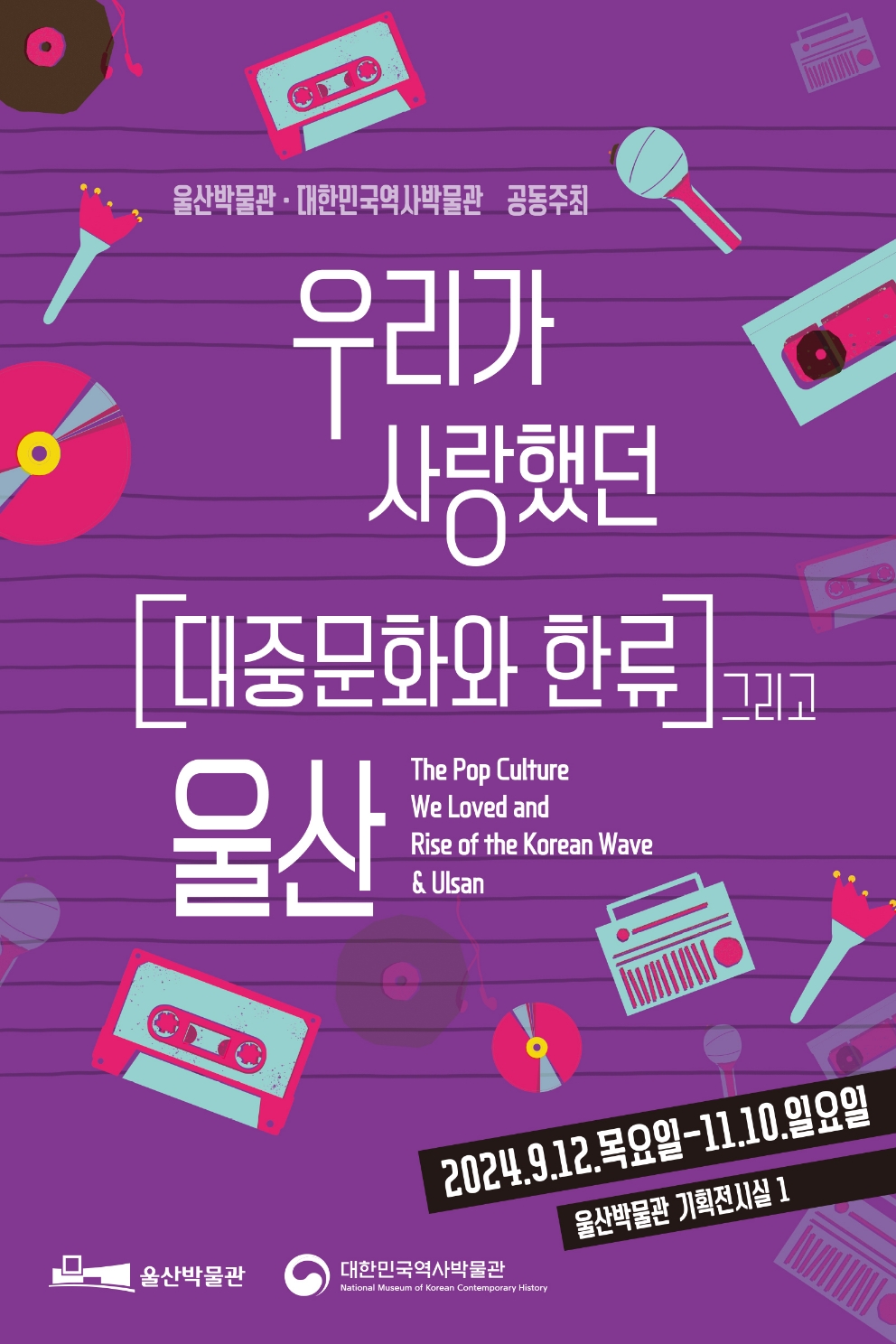

<Regional Collaboration Touring Exhibition> Special Korean Wave Exhibition at Ulsan Museum

This year, the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History began its first regional mutual growth tour exhibition. The regional mutual growth tour exhibition was designed to reflect the unique characteristics of each region rather than simply relocating popular special exhibitions held at the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History.

Following the first touring Korean wave exhibition, which was held at Gwangju Museum of History and Folklore in June, a second exhibition will be held at Ulsan Museum from September 12 to November 10. The exhibition, titled [Popular Culture and Korean Wave] We Loved, and Ulsan, will be held at Ulsan Museum’s Special Exhibition Hall I.

Digital Pamphlet for Cultural Institutions at Gwanghwamun

Much Toon

National Museum of Korean Contemporary History Newsletter 2024 Autumn (Vol. 74) / ISSN 2384-230X

198 Sejong-daero, Jongro-gu, Seoul, 03141, Republic of Korea / 82-2-3703-9200 / www.much.go.kr

Editor:Kim YangJeong, Jeong Suwoon

/ Design: plus81studios

Copyright. National Museum of Korean Contemporary History all rights reserved.